Mandatory Reporting; before we start criminalising we must do more supporting

Mandatory reporting is a contentious issue and is inherently problematic. The current government have been clear that they want to bring in a legal responsibility for people who work with children in England to report child sexual abuse or face prosecution. While I understand why this seems like a logical and positive progression, I am not convinced it is the right priority at this time.

In part, the government's position has been informed by Recommendation 13 of the final report of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. However, the report also acknowledges some of the complexities of this policy and provides caveats which require professional interpretation, further stating “caution must be exercised to ensure that the legislation works for the people it is intended to protect”.

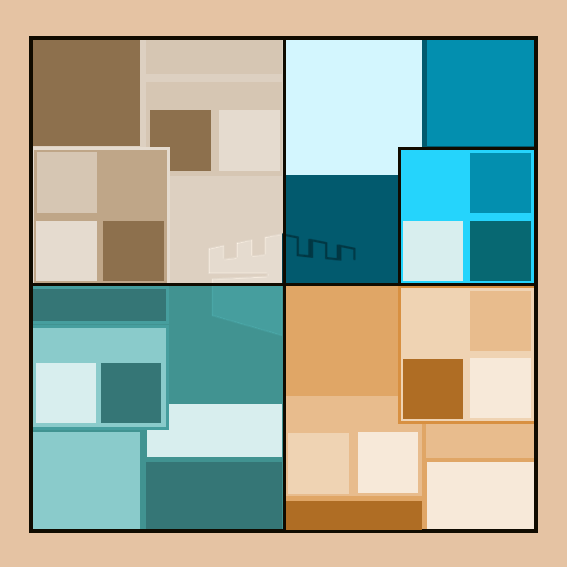

I think the most significant impact it may have on reporting rates is to make sure child protection is a little more in the forefront of practitioner’s minds, but I’m not aware of much evidence that our frontline practitioners are not reporting recognised indicators of sexual abuse. As must be the case with such pieces of work, the evidence used to support the recommendation of IICSA is from research of historical cases, and as a country, we are significantly more aware, proactive and conscientious when we see safeguarding concerns. Context is so important and to be most effective, we need people working with children and young people (and for that matter adults at risk) to look for changes in the context of those at risk and then be professionally curious, challenging what is presented at face value and asking questions to examine a child's situation from different angles.

The tragic stories of Victoria Climbie, Khyra Ishaq and Lauren Wright, are just three children who died at the hands of their abusers relatively early in our safeguarding awakening as a country. Alongside these, similar but recent tragedies such as the deaths of Star Hobson and Arthur Labinjo-Hughes, continue to find that professionals and practitioners were not supported effectively to be sufficiently curious and robust in their understanding of the situations of the children. The 2022 government report Learning for the future: final analysis of serious case reviews, 2017 to 2019 identifies three main areas of professional practice which remain problematic, one of which is a lack of professional curiosity and challenge. The report goes on to identify barriers to do with workload and time which limit practitioners from seeing sufficient context to trigger their professional curiosity.

I don't understand how mandatory reporting will fix that significant issue and am concerned that some practitioners will become fearful of asking too many questions in case they find out something they think they need to report and so might become less curious and less robust in their early safeguarding assessments.

Crimes are being committed in these situations by abusers, and I don't think blaming and criminalising practitioners alongside that is a helpful way forward. I can understand the arguments for it, but there are other priorities that need to be addressed as well, and I would argue these should be in place before we start seriously considering criminalising practitioners.

My experience tells me that social work front doors are usually supportive of advising professionals and practitioners who have concerns, but this could do with being formalised. When any practitioner has a concern about someone they are working with they should be able to pick the phone up to a safeguarding support worker (probably a social worker) to discuss the case confidentially and to receive advice.

Before we start criminalising how about we start supporting better?

For this to be formalised support there will need to be an increase in social work provision in all local authorities, but I think this could pay dividends. My Dad was a primary school headteacher in the 70’s – 90’s and during his career he insisted that a social worker was assigned to the children in his school and they would come in to school on a weekly basis to meet with staff and discuss safeguarding concerns. There isn’t the resourcing in social work to provide such a service these days but wouldn’t that be even better than having support at the end of a phone!

Practitioners, in all services, need to be led by people who are supportive about pursuing safeguarding concerns and who create organisations that take their collective responsibilities seriously, providing time and support for early safeguarding concerns to be raised, discussed and explored. So the priority in my mind is not mandatory reporting, it's getting every organisation that works with children, young people, and adults at risk to take their responsibilities seriously and support their practitioners (whether that’s social workers, teachers, school caretakers, sports coaches, youth workers or pastors etc) to be more curious and proactive in how they protect those they work with.

Working Together to Safeguard Children (statutory guidance issued under the Children Act 1989 and 2004) applies to statutory services "and other senior leaders within organisations and agencies that commission and provide services for children and families" and also says that "voluntary, charity, social enterprise, faith-based organisations and private sector" organisations "should have appropriate arrangements in place to safeguard and protect children from harm". The statutory guidance is already clear about this so rather than introduce new laws there needs to be greater emphasis on all organisations taking these responsibilities seriously. Much more in terms of resourcing safeguarding activity should be done in schools (giving teachers more time to pursue concerns), in social work and health services in (reducing caseloads/workloads) and in the police (increasing understanding of safeguarding as a key part of their role) but also in supporting other organisations to realise their responsibilities.

For this to happen, safeguarding needs to be prioritised by Boards and senior leaders and I therefore feel that if a legal responsibility is going to be put on anyone, it should be on the Board level leaders in organisations. If safeguarding issues are not managed appropriately within organisations (including a lack of reporting by individuals) and it can be proven that Boards didn’t take sufficient responsibility for understanding practice and were therefore either wilfully or deliberately negligent about it, I think they should be held accountable. Of course, all organisations are different with different resources and so we can’t expect significant investment which might put them out of business, and so their oversight and resourcing would need to be appropriate to their size and work.

Mandatory reporting seems to me to be like using sledgehammer to crack the wrong nut. I am not convinced that the negative impacts of that policy out ways the benefits and the priorities of increasing safeguarding resources and knowledge in statutory services and to reassert the existing statutory responsibilities on all organisations are a better way to proceed.

... and as an aside, if safeguarding is so important (which it is), the top Board in the country, the Cabinet of His Majesty's Government should have someone with named and explicit responsibility for safeguarding, supported by a government department. It seems to me that we need a dedicated Department for Safeguarding and Social Care, but that can wait for another day!